DEC newsCreating accessible housing requires a multi-faceted approach

The future of accessible housing for Australians with disability is an important and complex issue demanding attention and action from government, private industry and community organisations.

In recent years, significant efforts have been made to improve accessibility and inclusivity in the housing market, including through funding under the NDIS. There is still much work to be done, however, if we are to avoid the mistakes of the past, move away from models which may be ‘congregate care by any other name,' and create a vibrant and innovative disability housing market.

One of the main challenges facing Australians with disability is the obvious lack of suitable and affordable housing. This is partly due to an historical lack of government funding, as well as a lack of understanding and awareness among many developers and property owners.

Many people with disability are forced to live in overcrowded, inadequate or less-safe accommodation, such as boarding homes, or face the prospect of homelessness.

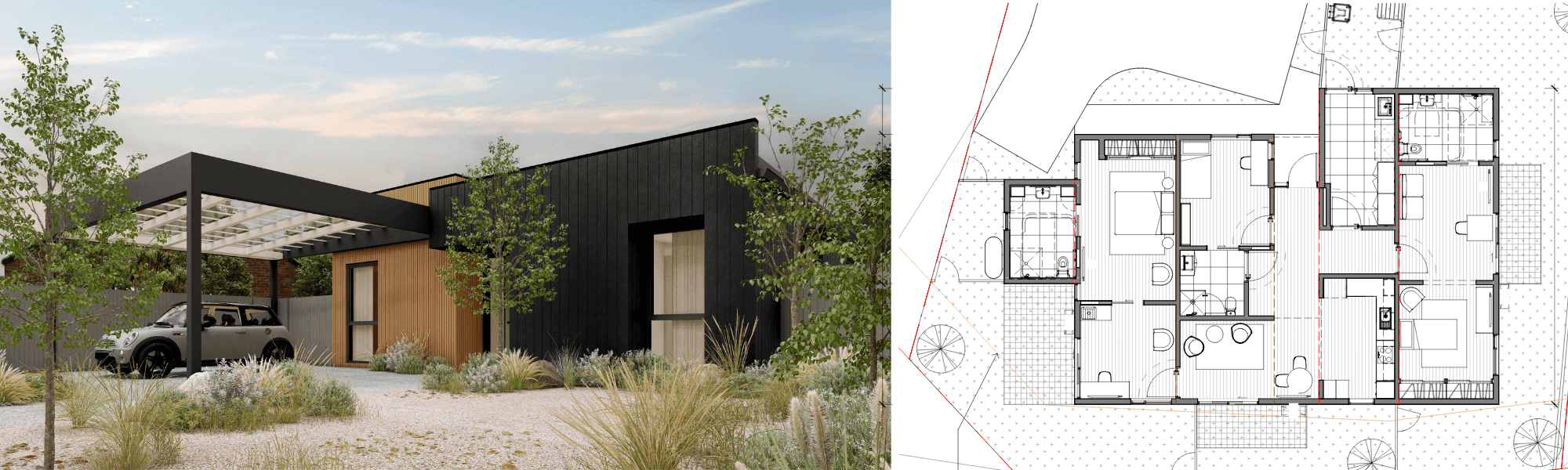

To address these challenges, governments must invest more in the construction and renovation of accessible housing. This investment would include funding for the construction of new housing developments specifically for people with disability (NB in ‘salt and pepper’ type arrangements) and grants and incentives for private developers to build accessible housing.

Additionally, government should provide funding for modifying and adapting existing group homes to make them accessible for people with disability, the quid pro quo being that group homes should not receive any funding for modification unless the work includes reducing the number of bedrooms for residents to not more than three. If this is a step too far for the sector, the approach described above should be grandfathered to give providers reasonable time to adjust, both financially and operationally.

A critical step on the path to housing justice for people with disability is to increase awareness and understanding of the needs of people with disability among private developers, property owners, and real estate agents. This could be achieved through education and training programs and by introducing nationally uniform guidelines and standards for accessible housing.

Regarding the issue of guidelines, it’s true that in 2022, the Federal, State and Territory Governments came together to agree on the introduction of new Liveable Housing Design Guidelines (LHDG) into the National Construction Code for implementation in 2023. These Guidelines will mean that new home builds will be accessible to a wider range of people and that new homes must incorporate seven key elements to meet minimum accessibility standards, including step-free entries and easy access bathrooms.

However, it is also clear that governments’ responses to these new Guidelines is not yet uniform. NSW and WA are yet to agree to adopt minimum accessibility building standards as part of the Code, out of concerns about additional building costs, which would be passed on to the client/resident. These concerns are apparently not shared by the other governments. On a related point, there is serious policy work to be done, in consultation with the sector and people with disability, to determine how SIL providers can sustainably support NDIS participants with behaviours of concern to live independently.

The support required by these NDIS participants calls for a different level of skill; but Houston, we have a problem! The sector doesn’t have enough workers with the necessary expertise and experience. Bridging this gap will likely be expensive, requiring new funding from governments for training, work placements and employment.

Other issues demanding attention, if disability-accessible housing is to be treated as a right and not a privilege, must include positive outcomes from the review of SDA Pricing under the NDIS.

As things currently stand, the cost of construction and land in most parts of Australia means it’s very difficult, if not impossible, to make new SDA – Improved Liveability and Fully Accessible stack up financially within a 25 km radius of the capital cities. At the same time, measures to make access to land easier for SDA providers willing to undertake ‘new builds’ should be implemented consistently across Australia.

The period of time when Medium Term Accommodation may be occupied should be extended to 180 days, better allowing people with disability to transition seamlessly from their current abode (for example, a group home or hospital) to more permanent, customised accommodation, which offers them the ability to ‘age in place’ should they wish.

And in regard to finding a housemate(s) with whom a person with disability wants to live, we need to explore the capacity of technology, including AI and machine learning to assist in making this experience more ‘hit’ and less ‘miss’ for all involved. The days of people with disability being ‘decanted’ like an old bottle of wine should be consigned to history if they haven’t been already.

Housing is a fundamental human right, and governments must proactively ensure that people with disability are not left behind in gaining fair access to the housing market.

Overall, the future of housing for people with disability in Australia requires a multi-faceted approach that includes government investment, private sector engagement, and community support. By working together and adopting progressive, sensible housing policies, we can create a more inclusive and accessible housing market for all Australians.